Art > Sculpture

Sculpture

Sculpture

By the time I discovered the artist lurking inside me, I had already traveled many life miles, literally and figuratively.

I immediately dedicated myself to intensively learning materials and methods of creation. You see here guideposts on my route to social practice art. At first I explored form through drawing, stone carving and clay. Then I began to add in meaning. Now, in addition to form and meaning, my art practice incorporates its viewers, evident with my major art series.

2015

Khe Sapa

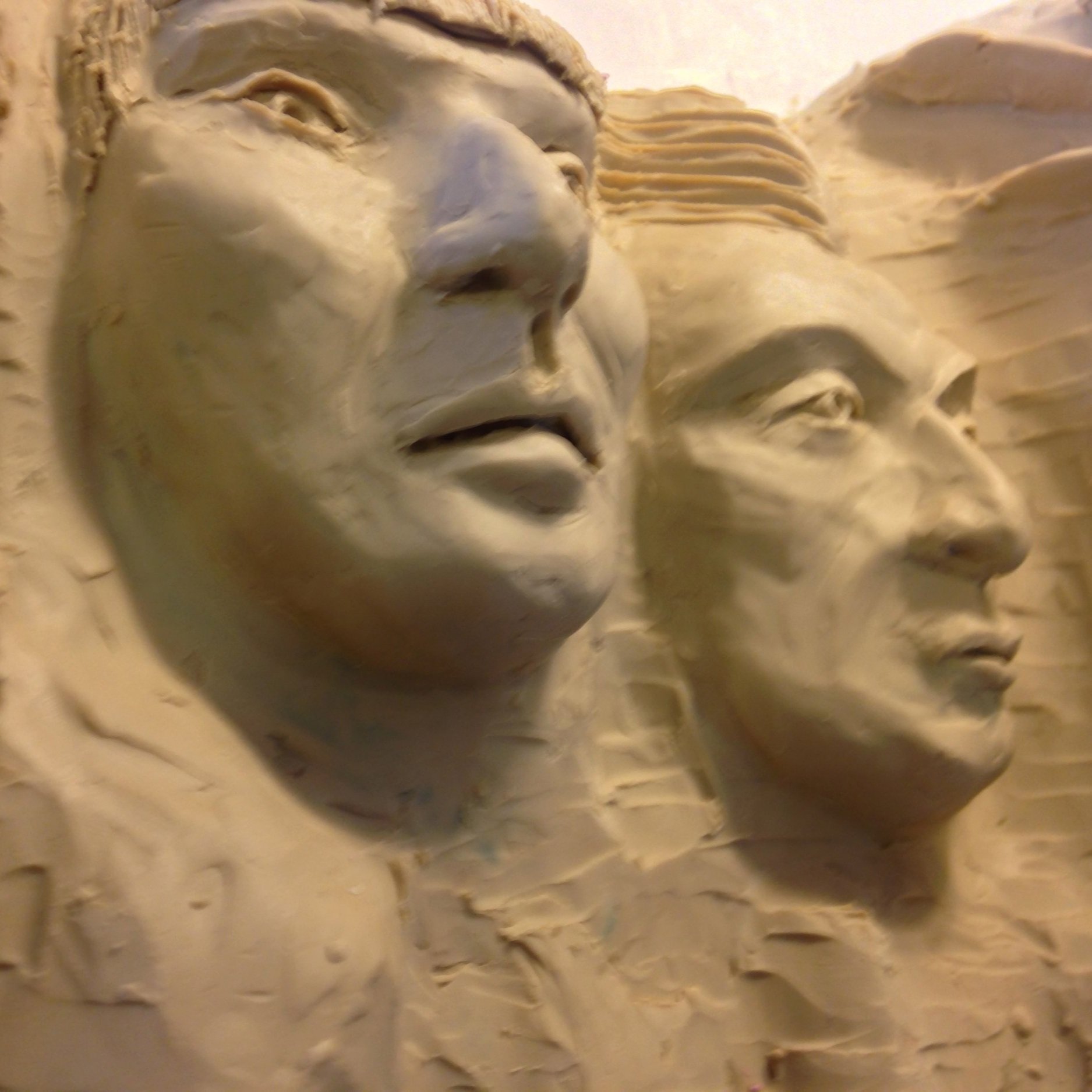

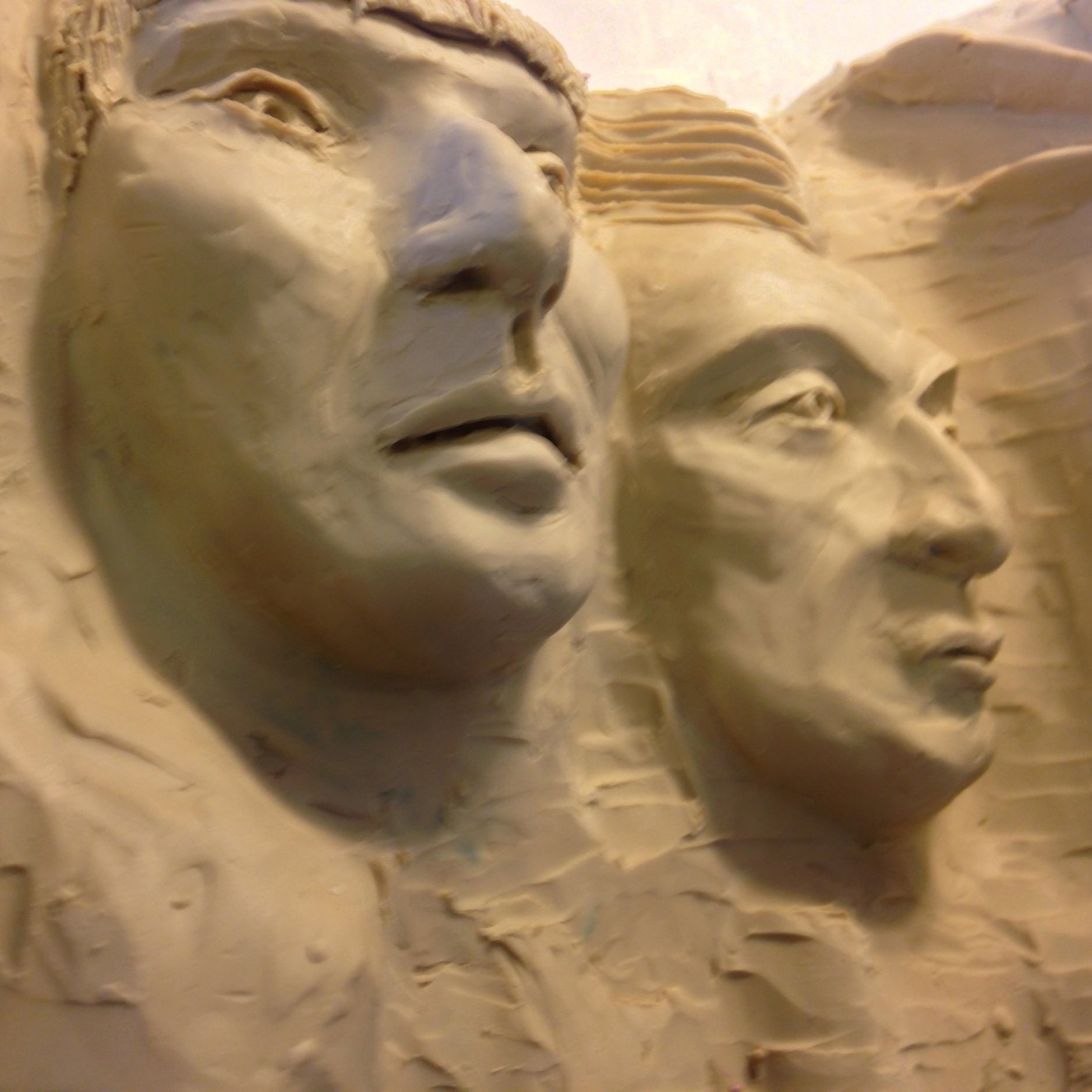

The 1868 Fort Laramie treaty returned the Black Hills of South Dakota to Native Americans. Six years later, when an expedition led by General Custer found gold, the treaty unraveled. Fifty years after Congress officially broke the treaty, the carving of Mt. Rushmore began, indelibly claiming this sacred land.

I created Khe Sapa, (Lakota for Black Hills) to transform the known monument into a more just commemoration of Native American leaders. This artwork is cast in ice, its temporal existence — and the dominance of Native American culture — as fleeting as Mt. Rushmore's granite countenances are permanent.

2015

Khe Sapa

The 1868 Fort Laramie treaty returned the Black Hills of South Dakota to Native Americans. Six years later, when an expedition led by General Custer found gold, the treaty unraveled. Fifty years after Congress officially broke the treaty, the carving of Mt. Rushmore began, indelibly claiming this sacred land.

I created Khe Sapa, (Lakota for Black Hills) to transform the known monument into a more just commemoration of Native American leaders. This artwork is cast in ice, its temporal existence — and the dominance of Native American culture — as fleeting as Mt. Rushmore's granite countenances are permanent.

Converse/Converse

Black and white agate

Sun/Son

Cast aluminum

Privilege

Bronze

We the People

In one of its first acts, the Trump administration (2017) worked to ban immigration from six predominantly Muslim countries.

As a sign of resistance to Brexit, some Brits displayed safety pins on their clothing. This practice was adopted in some parts of the United States in response to the 2016 election. With sculpture, every material choice communicates using visual and symbolism language unique to it.

Give us your tired, your poor, but not your Islamists.

We the People

In one of its first acts, the Trump administration (2017) worked to ban immigration from six predominantly Muslim countries.

As a sign of resistance to Brexit, some Brits displayed safety pins on their clothing. This practice was adopted in some parts of the United States in response to the 2016 election. With sculpture, every material choice communicates using visual and symbolism language unique to it.

Give us your tired, your poor, but not your Islamists.

Belvedere Torso

Clay

Composed

Clay, paper

Evolution

Soapstone

Surplus

Are unhoused people really "surplus"?

Hurrying to my car one afternoon, I stepped out of my way to avoid a homeless man sprawled on the sidewalk. Once I was seated in my car, hands clutching the steering wheel, my annoyance at the man melted into embarrassment and shame. I cared more about having a clear sidewalk than about a suffering fellow human being. How insidiously twisted our values become when extruded through the press of our daily, busy lives.

And thus was born Surplus. How perfectly apt to fashion a sidewalk segment out of a homeless man’s blanket, its material suppleness mirroring the vulnerability of human flesh, while conjuring the body of a reclining homeless person with concrete rubble and rebar from a Chevy Chase sidewalk, itself shattered and displaced.

Surplus

Are unhoused people really "surplus"?

Hurrying to my car one afternoon, I stepped out of my way to avoid a homeless man sprawled on the sidewalk. Once I was seated in my car, hands clutching the steering wheel, my annoyance at the man melted into embarrassment and shame. I cared more about having a clear sidewalk than about a suffering fellow human being. How insidiously twisted our values become when extruded through the press of our daily, busy lives.

And thus, was born Surplus. How perfectly apt to fashion a sidewalk segment out of a homeless man’s blanket, its material suppleness mirroring the vulnerability of human flesh, while conjuring the body of a reclining homeless person with concrete rubble and rebar from a Chevy Chase sidewalk, itself shattered and displaced.

Dead Sea

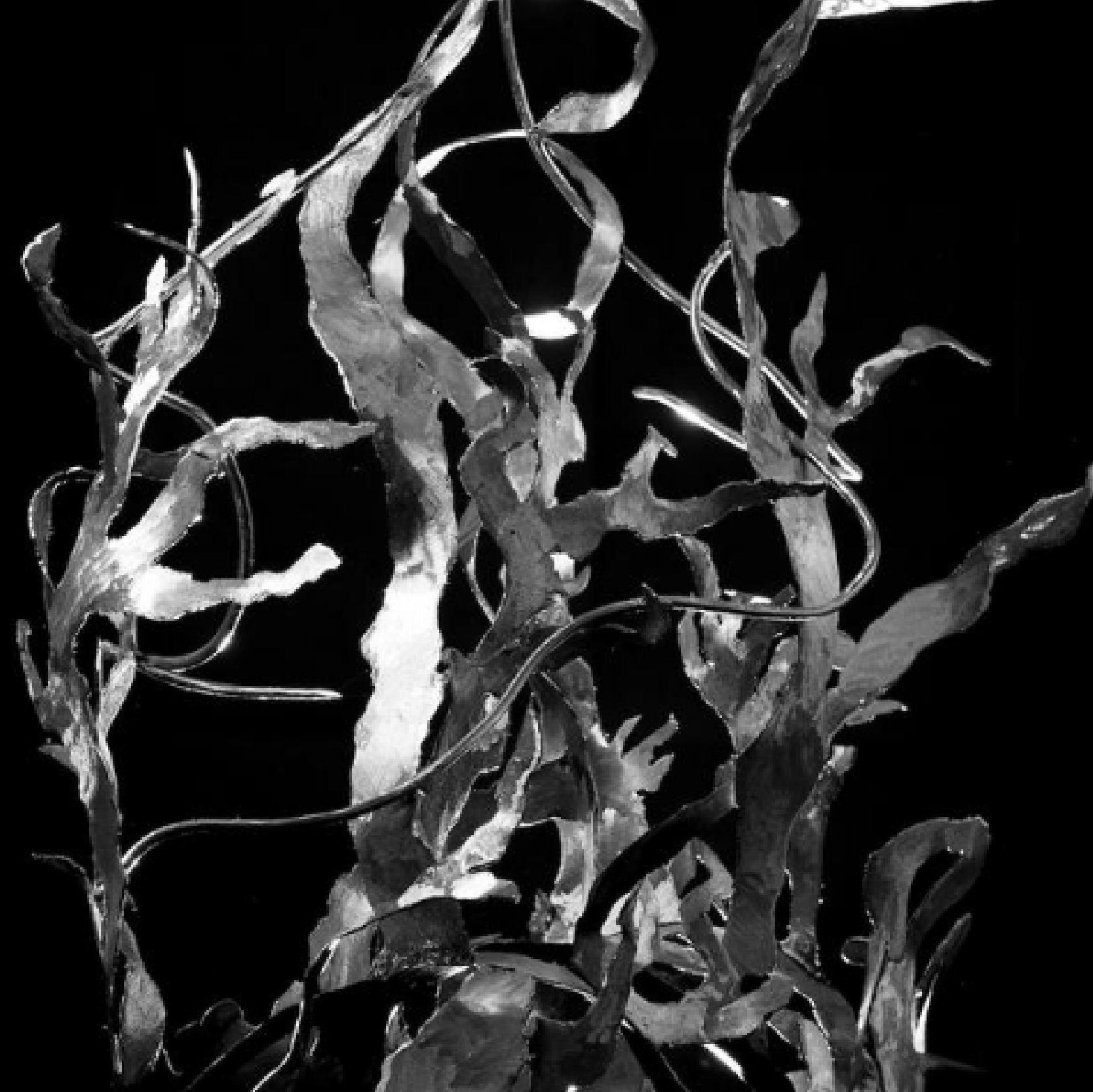

Dead Sea speaks to the devastation of our oceans. This was a learning piece for me — learning welding, learning use of a plasma torch, learning how important the title of an artwork can be for the power of the piece.

Dead Sea

Dead Sea speaks to the devastation of our oceans. This was a learning piece for me — learning welding, learning use of a plasma torch, learning how important the title of an artwork can be for the power of the piece.